The improbable, fantastic, (somewhat) true life of Jilson Setters

- Jeff Kidd

- Mar 28, 2016

- 4 min read

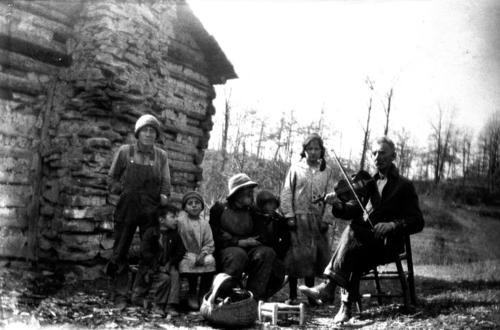

“In a windowless cabin, hidden away in a high cranny of the Kentucky mountains, lived Jilson Setters, who, for all his sixty-five years, had never seen a railroad. Neither had he heard a phonograph nor a radio. His home-made fiddle and his ‘ballets’ were good enough for Jilson Setters and mountain folk.”

“The Last Minstrel” by Jean Thomas, The English Journal, Dec. 1928

Bill Day's musical career was launched on fiction, but what followed was far more strange: A blind man made to see; a self-taught fiddler recording for a major label; a beggar performing for royals.

If you've heard at all of my first cousin three times removed, you probably recall him by his stage name, Jilson Setters. That's what he was called when he traveled to London in 1931 to perform at Royal Albert Hall, and for King George V and Mary of Teck.

But it's more likely you've never heard of him at all. I can think of no better introduction than his music.

I stumbled upon Day's story while researching another relative, renowned Progressive-era, adult-literacy advocate Cora Wilson Stewart. Like my parents, they were born and raised in and around Rowan County, Ky. I had no idea I was related to Day, but as I listened to a few YouTube videos featuring his songs, I recalled seeing a Day or two in my family tree. It took only a few hours of poking around on Ancestry.com to trace the relationship — Bill was the first cousin of my 2G maternal grandmother.

Easy enough. But separating fact from fiction was a bit more challenging.

Many of the widely circulated accounts of Day's life were taken or derived from tales spun by his manager, Jean Bell Thomas, an amateur folklorist, professional Hollywood writer and ... maybe .... a circuit-court stenographer traveling through Rowan County when she came upon "Blind Bill" Day playing outside the courthouse. I say "maybe" because I've seen stories asserting that is indeed how she discovered Day and other accounts implying this was part of the backstory she created largely from whole cloth.

Here's what I think I know about him.

James William Day was born in Cattlesburg, Ky., in 1861. He wasn't born blind, but at some point early in his life, he suffered an impairment, possibly cataracts, that robbed him of his sight. He taught himself to play the fiddle, sometimes performed under the stage name "Blind Bill Day" and occasionally supported himself by begging. In 1906, Day had a procedure to remove the catracts, restoring his eyesight.

That was 20 years before Day discovered him — and supposedly sprung for the surgery that allowed him to see again.

Whether Day was literally singing for his supper when Thomas first encountered him, and whether that encounter was actually outside the Rowan County Courthouse, where Thomas was working as a stenographer, I'm uncertain. But Thomas had indeed worked for a time in Hollywood and indeed had a fascination with rural folk musicians. Thomas decided to manage Day, often billing him as the "Singin' Fiddler of Lost Hope Holler."

Of course, there was no such place as Lost Hope Holler.

Thomas also claimed that Day had been blind from birth, that she provided the surgery that restored his eyesight and that he changed his name per her suggestion. The part about his name might have been the case, but if so, Thomas hardly pulled the name from thin air — "Jilson" was the first name of Day's father, and "Setters" was his mother's maiden name.

And that introductory quote to this article, the one that claims ol' Jilson had never seen a railroad? Highly unlikely. The Elizabethtown, Lexington and Big Sandy Railroad was operating in Rowan County by the 1880s, with tracks running through the edge of Morehead, no more than a few hundred yards from the courthouse where Thomas supposedly discovered Day.

According to a Wikipedia entry Day, Thomas published a heavily fictionalized article in American Magazine, "Blind Jilson: Signing' Fiddler of Lost Hope Hollow," detailing their arrangement of his operation and radio station work in New York City. Nonetheless, the article states that Setters recorded "The Wild Wagoner" for the Library of Congress, a rendition later included in a 1952 Anthology of American Folk Music.

That, indeed, happened.

So did Setters' 1931 trip to London arranged by Thomas, and his performance at Royal Albert Hall for King George V. Upon his return to the United States, Day also was the featured performer in the American Folk Song Festival managed by Thomas. (Among the festival's board members were Carl Sandberg and Ida Tarbell. Incidentally, Tarbell was also an adviser to Cora Wilson Stewart's adult-literacy crusade.)

A description of the festival in Time Magazine included this passage:

Because many an expert believes that these are the rarest of U.S. folksongs, cameramen were present to film the proceedings for the Library of Congress. Feature of the afternoon was supposed to be an Elizabethan wedding celebration in which Marion Kerby, Chicago ballad expert, soloed.

But outsiders were more interested in Jilson Setters, the 75-year-old fiddler whom Miss Thomas took to London a year ago to perform in Albert Hall. Jilson Setters has earned wide publicity for Miss Thomas' folksong society. When he arrived in Manhattan to sail, his baggage consisted of one extra shirt, a quilt his grandmother had made, a gourd for a drinking cup, a corncob pipe and his fiddle wrapped in an oilcloth poke.

He came, he said, from Lost Hope Hollow and he was going to see the King. Ashlanders have since said that there is no such place as Lost Hope Hollow, that Jilson Setters' real name is William Day, never much of a mountaineer, but an old-time beggar.

Thomas continued to manage the festival until 1972, but she and Day apparently parted ways long before that. I'm not sure why. There is some indication that the folks back home resented Thomas' over-the-top stories about Day's upbringing and way of life, which cast them as hillbillies. It also is possible that Day's recordings and his live act simply did not sell well and Thomas needed to move on.

Setters continued to perform into the 1930s. He died of a cerebral hemorrhage on May 6, 1942, near Ashland, Ky.

Comments